Breaking down the guideposts, or at least a few

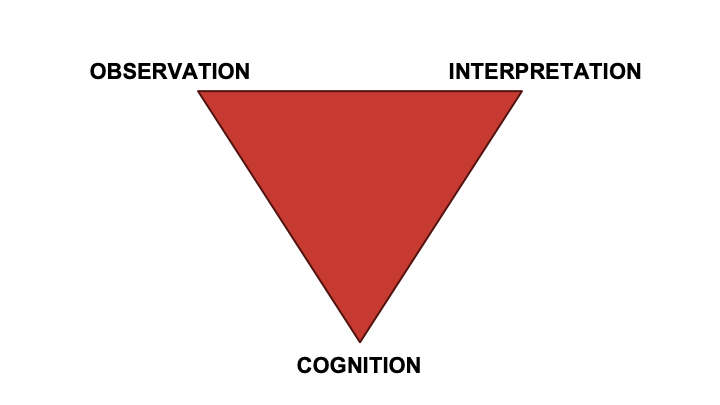

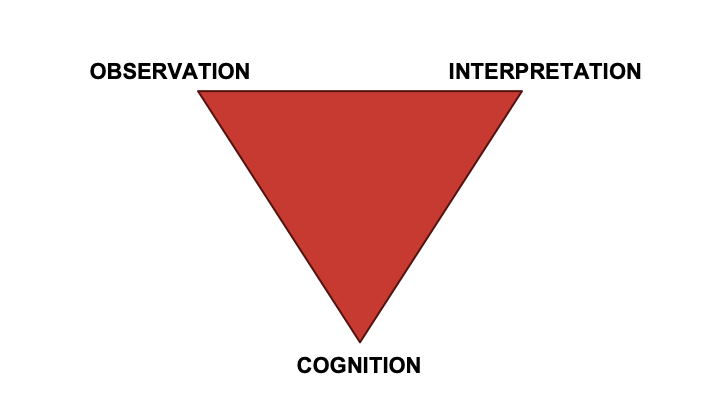

This is the assessment triangle. It emphasizes the importance of coherence between what is being assessed, as in what aspect of cognition or thinking, how that cognition will be observed, and how resulting data will be interpreted.

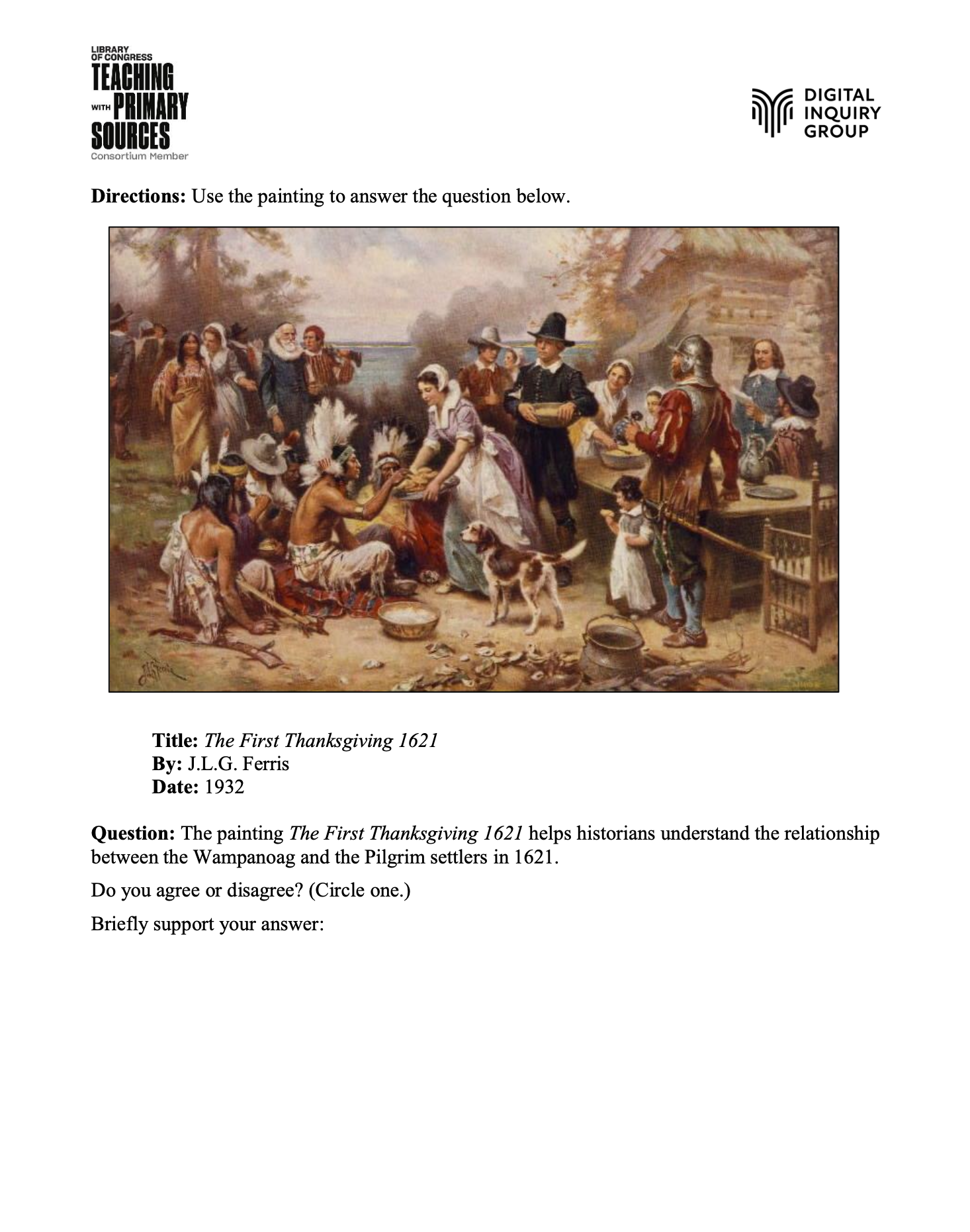

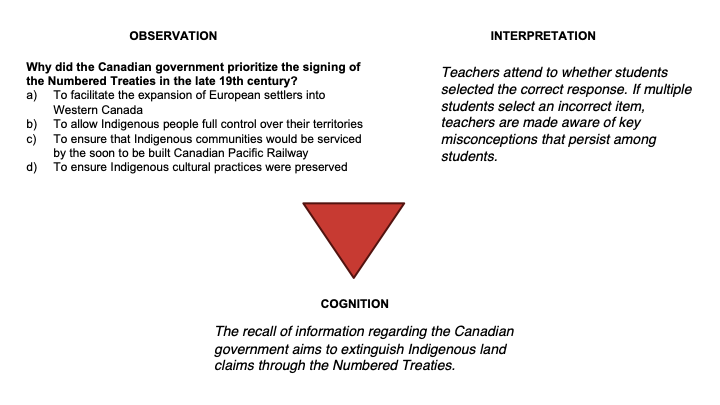

In a history classroom that emphasizes an understanding of key dates, people, events, or issues, achieving coherence within the assessment triangle is somewhat straightforward. The aspect of cognition often targeted is the recall or description of this information an can be observed through a variety of selected response items(ie. multiple choice, matching, fill in the blanks), or more developed constructed responses, such as a short answer question. These approaches both are relatively straightforward to interpret, as either students have identified the correct response, or have described the key or relevant information in their response.

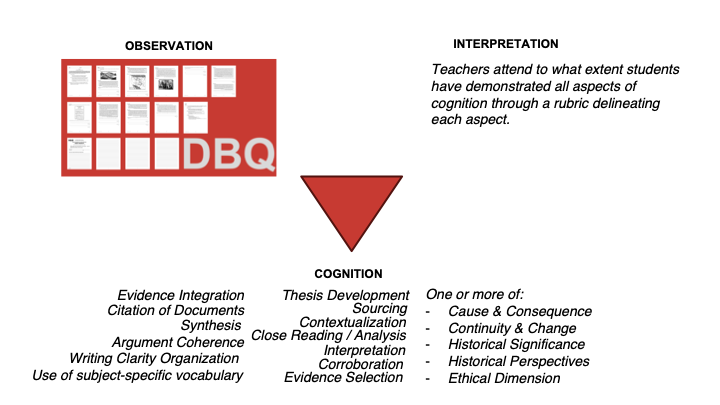

In a history classroom emphasizing the development of historical thinking, that is, introducing and having students practice working with the epistemology of history, achieving coherence within the assessment triangle is somewhat straightforward. Document-Based Questions (DBQs) have typically been seen as the best route as they require students to engage directly with primary and secondary sources to construct evidence-based arguments. DBQs assess skills such as sourcing, contextualization, close reading, corroboration, which are central to understanding how historical knowledge is constructed. Through this practice of interpretation, students demonstrate, and are reminded of complexity and subjectivity inherent in the study of history.

And DBQs are useful tools, if we are aiming to gain a macro view of student engagement with the epistemology of history. But if we were to dig a bit deeper into the bottom point of the assessment triangle and actually tease out what is being assessed, we’d find an abyss of possible learning goals being targeted.

This places some wild expectations on a rubric that is going to capture student performance on all of those aspects…perhaps thus our constant revising of rubrics that never seem to satisfy.

“it’s hard to know what the DBQ actually measures.”Wineburg, Smith, & Breakstone

I believe that the assessment that I have provided and continue to provide students has been, to the best of my power, generally fair, and broadly accurate in its judgment of student skills and abilities. But as Smith and Breakstone from the Stanford History Education Group suggest, it’s difficult to tell just what exactly a DBQ is measuring. Or perhaps the problem is that we know what it is measuring: everything. As a macro-summative task, it’s the best we got. However as a formative tool, entirely unwieldy. Sifting through a student response to truly assess student performance on individual constructs which are folded in and upon one another is an incredibly time consuming process for members of a profession who lack exactly that.

So Smith and Breakstone went to work. The Stanford History Education Group, now rebranded as the Digital Inquiry Group, has lead the way in the United States for pioneering small-scale formative assessments intended to be more precise or surgical, targeting individual historical thinking heuristics and skills more specifically in order to build up individual skills prior to students taking on more complex demonstrations of historical thinking such as a Document Based Question.

Unfortunately, but not unsurprisingly, Canadian history does not feature much in the assessment tasks developed by DIG.

And so I got to work. I began to adapt these assessments to the content that I was teaching in BC Social Studies 9 and 10 courses. I also was keen to approach the development of these tasks using the Big Six Historical Thinking model theorized by the late Peter Seixas that has been adopted by provincial and territorial curriculum across Canada.

To narrow the focus, I chose to concentrate on the benchmark of Evidence, as it is particularly central to disciplinary inquiry. While we might explore problem spaces such as significance or cause and consequence, all claims of consideration in these other benchmarks must return to the historical record.

In their formulation of Evidence inThe Big Six, Seixas and Morton outline 4-5 guideposts—specific skills or understandings considered essential for analyzing, interpreting, and constructing arguments based on historical evidence.

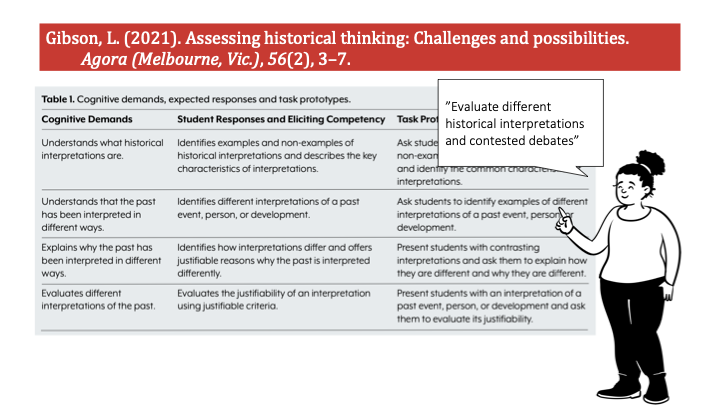

Then I got deep in the weeds. Using the example that UBC’s Lindsay Gibson provided in his article “Assessing Historical Thinking: Challenges and Possibilities” I attempted to breakdown each guidepost in a similar manner in which he did with the Victorian History Curriculum item: ‘Evaluate different historical interpretations and contested debates’ To evaluate different historical interpretations and contested, one must know what an interpretation is. Understand that the past has been interpreted in different ways, and can explain why as well. Thus we create a type of taxonomy leading up to our original curriculum item.

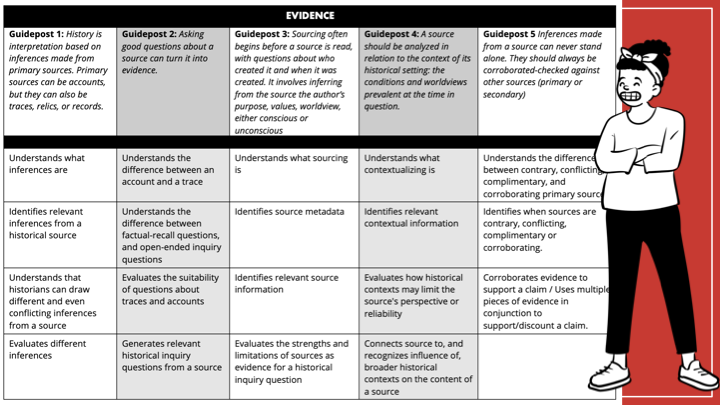

Here’s what that looked like with the guidepost of Sourcing. I attempted to identify the specific competencies, sometimes called constructs, that I might target. These would be the cognition point of the Assessment Triangle.

Guidepost 3: Sourcing often begins before a source is read, with questions about who created it and when it was created. It involves inferring from the source the author’s purpose, values, worldview, either conscious or unconscious.

- Students will be able to:

- Understand what sourcing is

- Identify source metadata

- Identify relevant contextual information

- Infer regarding purpose, values, or worldview of source author

- Evaluate the strengths and limitations of a sources as evidence for a specific historical inquiry

Then I did the same with each of the other guideposts within the benchmark of Evidence.

As you can see, it quickly become a fairly unwieldy monster.

Especially given that applying this process to the other benchmarks in The Big Six would result in an overwhelming 100 specific constructs to assess. This didn’t seem like a solution. It seemed like a problem.

And yet, I found the process particularly revealing. It illuminated broadly the type of understandings and skills required for sophisticated work within the benchmark of Evidence, and as a teacher that was useful. I had no intention of assessing each individually with my students. But with this created roadmap this I could use my professional judgment to decide which avenues or streets would be best to travel through, to prioritize certain items I felt were more critical and/or that I believed held some rich possibilities for assessment.

And by breaking down the individual understandings or skills needed to effectively engage in historical inquiry, students could be provided with short formative tasks on a regular basis that illuminated the epistemology of history in a transparent manner, and be provided with regular feedback on how to more effectively work with evidence prior to engaging in more robust historical inquiry.

The process of entangling an intricate web of skills and understandings helped me orient myself within the benchmark of evidence, and from here I could begin to start designing assessments.

More on that in our next post.