The Starting Point – The First Thanksgiving

When beginning to draft the first Canadian History Assessments of Thinking, the most obvious space to explore for inspiration was the Stanford History Education Group’s (now Digital Inquiry Group) Beyond the Bubble Assessments. A collection of “140 easy-to-use assessments that measure students’ historical thinking rather than recall of facts”, the Beyond the Bubble assessments aim to assess key historical thinking competencies such as sourcing, contextualization, close reading and corroboration.

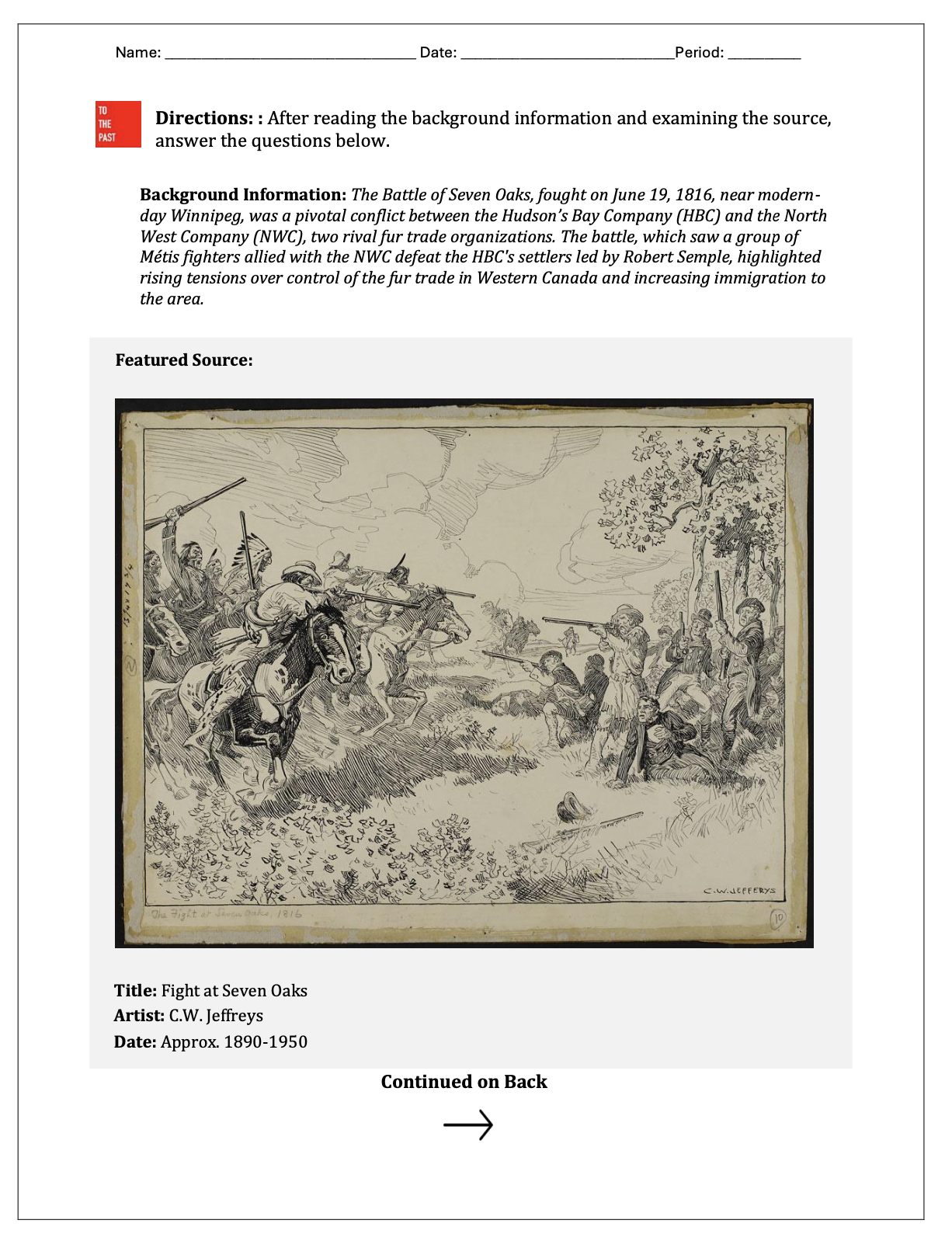

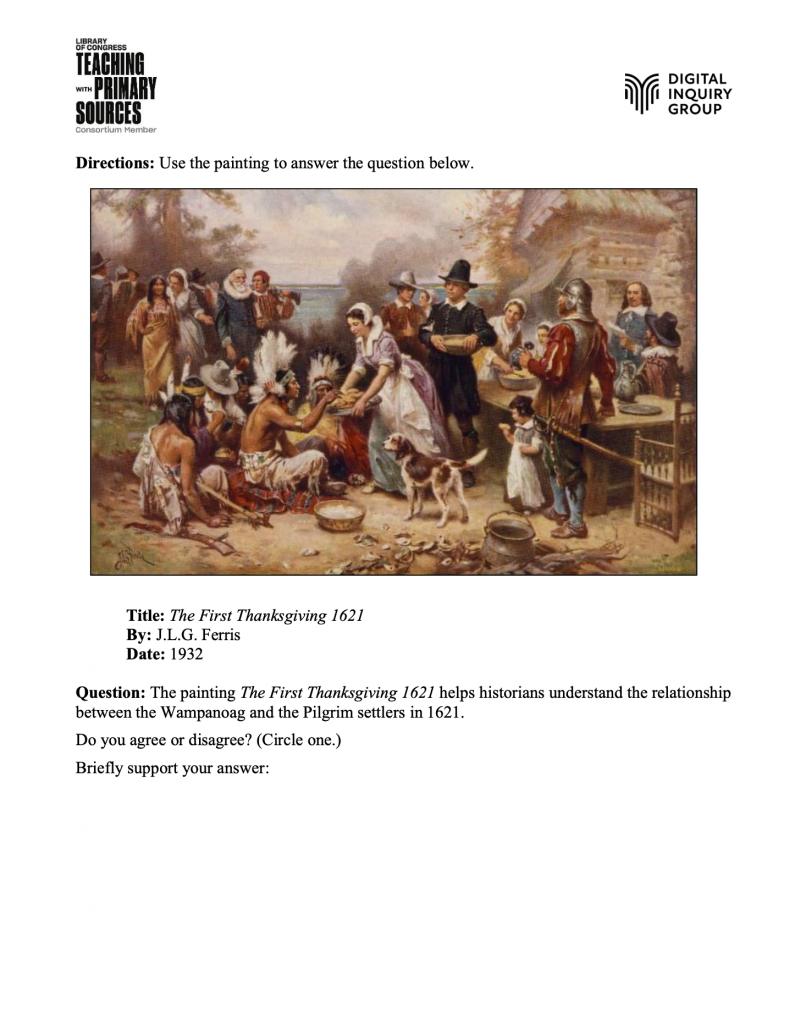

Perhaps their most well-known is one of their flagship models, “The First Thanksgiving”. At its root, The First Thanksgiving aims to illuminate for teachers whether or not students are attending to the metadata of a source, in this case, a painting. Students are challenged to note the discrepancy between the event date and time of the source’s creation, and how that might impact the helpfulness of the source as evidence of what happened during the original event.

Breakstone (2013) details the experience of several teachers using J.L.G. Ferris’ painting, The First Thanksgiving and other parallel assessments with the same structure (but different substantive content). He notes that in initial iterations nearly all students failed to attend to the limitations suggested by the date of the source. Upon reviewing the assessment and taking up the mantra of “source first” as suggested by their teachers, all students in subsequent parallel assessments were dutiful in noting the gap between the event depicted and the date of the source’s creation.

The First Thanksgiving: Adapting to Canadian History Events

In my first glance at the assessment, it was easy to notice how simply it would be to create such an assignment for Canadian history teachers who might not regularly focus on the first thanksgiving between pilgrim settlers and the Wamanoag. Simply swap out “The First Thanksgiving” for any painting depicting a event commonly (or uncommonly) taught in Canadian history and ask the same question!

But something nagged at me about the assessment. In the way it was structured, students were essentially being tasked to identify whether this was a primary source or secondary source. But baked into this identification is the assumption that, for historians, primary source = helpful / secondary source = unhelpful. However, I doubt that those at the Digitial Inquiry Group would suggest that Nathaniel Philbrick’s Pulitzer Prize finalist Mayflower: Voyage, Community, War or any recent peer-reviewed manuscripts regarding early pilgrim settlers in North America are not helpful for historians because they were published in the 21st century.

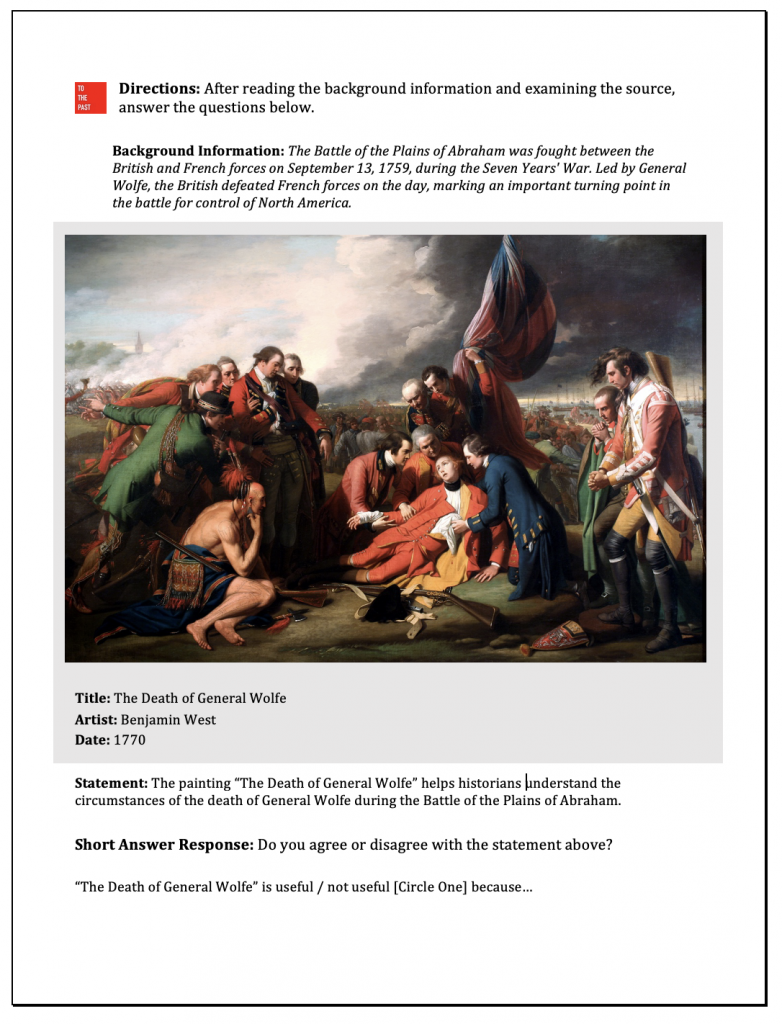

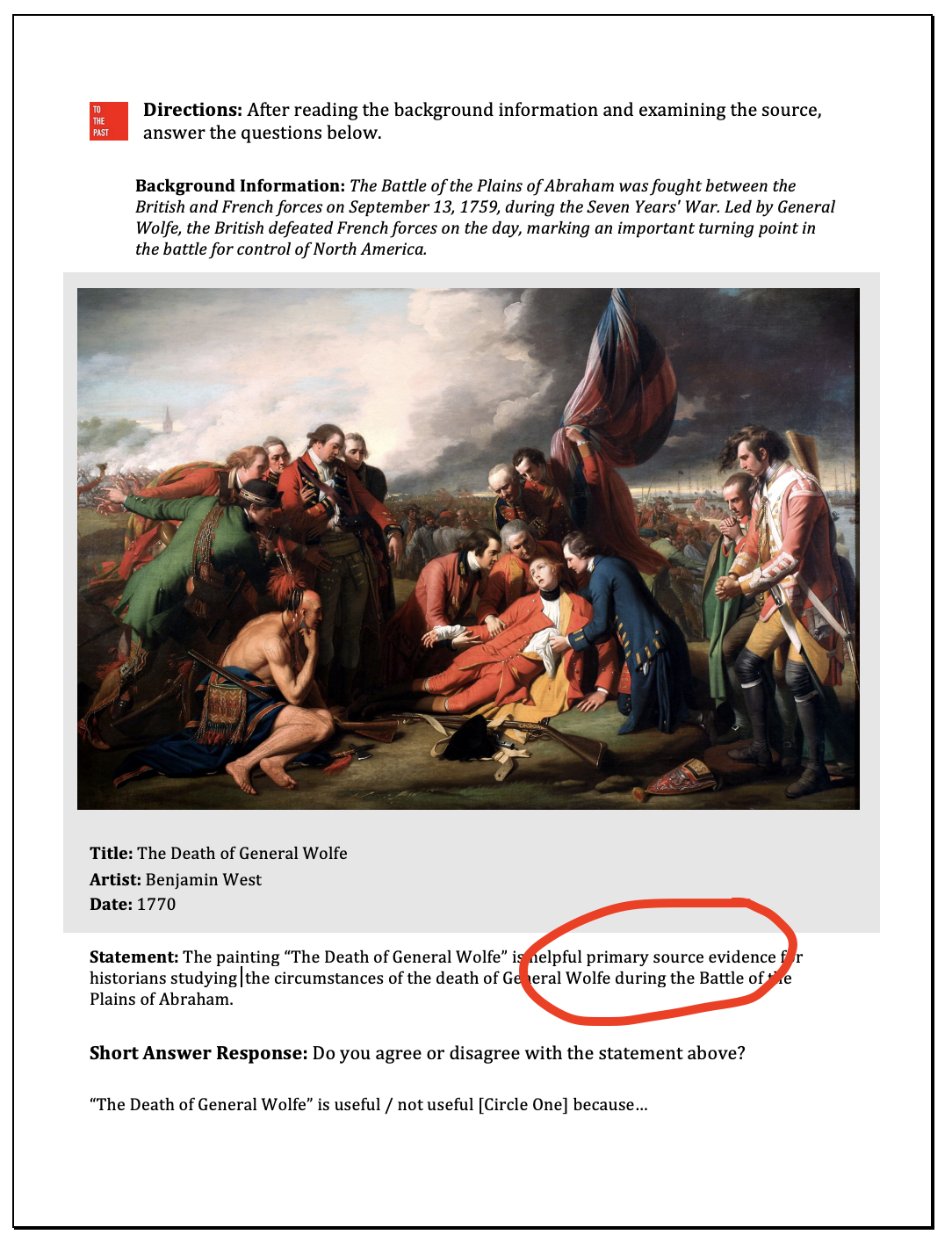

Perhaps a deeper level it rests on assumptions, regarding the different expectations we have for visual and text-based sources. While Benjamin West, famed painter of The Death of General Wolfe argued “the same truth that guides the pen of the historian should govern the pencil of the artist,” most have seen enough romanticized or blatantly false historical paintings to know that this is not always the case. However, if Ferris had spent decades in the archives, conducting meticulous testimonial analysis, culiminating in a masterpiece depiction of The First Thanksgiving…would we see the time elapsed as problematic and rendering the source “not helpful”?

The best answer to The First Thanksgiving short answer question is probably “I don’t know. I don’t know the expertise of the source creator or the extent to which they researched the event depicted, and therefore it is difficult to make a judgment regarding this source’s helpfulness”.

The First Thanksgiving: Variations on a Theme

Regardless, I have used First Thanksgiving style assessments in my classroom. However I did make one adjustment. Instead of asking if the painting was a helps historians, I now ask whether it is “helpful primary source evidence”. I think it’s a little more fair and a little more at the heart of what the original First Thanksgiving was asking for.

This will still likely result in an unthinking liturgy of “Ah yes, this looks familiar. Another painting or illustration. The date of the source’s creation is many years after the time being depicted. Therefore, while the uninitiated might view this as a primary source, it is actually a secondary source and because we do not know the expertise or research conducted by the source creator, it is difficult to judge its faithfulness to the historical record.”

However I am committed to not letting perfect become the enemy of good. Again, acccording to SHEG’s research, using this type of assessment resulted in students more regularly identifying the metadata of the sources they analyzed. I’ll take that as a net positive.

I even played with a two source option which you can find here:

The First Thanksgiving: Further Variations on a Theme

However I did want to explore some other variations that might avoid another possible consequence of using The First Thanksgiving. While the question suggested by SHEG clear directs students to assess the helpfulness of a source for a particular question or inquiry, ie. the relationship between Wampanoag and the Pilgrim settlers in 1621, students may come to the conclusion that the painting they are looking at entirely or broadly not helpful or useful at all to historians.

However the usefulness or helpfulness of evidence depends on the questions being asked by the historian. If one were to ask how American’s have depicted , portrayed, and commemorated settler-colonial relations through time, J.L.G. Ferris’ painting would be particularly revealing evidence and dismissing it would be a significant misstep.

The following is an attempt to specifically target the last of the concerns mentioned, that of the usefulness of evidence being profoundly connected to the questions being asked of it.

Using the heavily romanticized portrayal of the death of General Wolfe by Benjamin West (again created decades following Wolfe’s passing). Students are provided with the following statements and asked, “Which of the following statements do you disagree with?”

- Statement 1: The painting “The Death of General Wolfe” is useful evidence to understand how the event of General Wolfe’s death was remembered and commemorated in the 18th century.

- Statement 2: The painting “The Death of General Wolfe” useful evidence to understand the circumstances of the death of General Wolfe during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

- Statement 3: The painting “The Death of General Wolfe” is useful evidence to understand the artistic techniques, styles, and cultural and political trends/ideas of the 18th century.

Once complete, they are asked to explain their decision in a short answer item. As can be noted, the structure of statement 2 is pulled directly from “The First Thanksgiving” assessment. Students should again identify that the time elapsed between the creation West’s painting and the event it depicts makes this a secondary source making this statement difficult to support. However, student responses to statements 1 and 3 may reveal student understanding of how a source could be both useful and not useful to a historian, depending on the questions they are asking of it.

While not perfect, this assessment still provides teachers with insight into how students are conceiving of the strengths and limitations of a source. Discussing student responses provides an opportunity to delve into how the effectiveness and limitations of evidence are linked to the types of questions raised about it.

Even imperfect assessments have the potential to open up rich conversations about key historical thinking competencies or habits of mind.