In our previous post, I described how typical historical thinking assessments such as DBQs might just be assessing too much at one time, and that we would do well to break down the component skills, heuristics, or habits of mind of historical inquiry and conduct frequent assessments and conversations regarding sourcing, contextualization, close reading, and corroboration. Through this process we might better scaffold the learning process for students as they made their way towards more macro demonstrations of understanding.

I may have made it seem like I knew what I was doing. But attempting to actually design assessments that more surgically targeted specific historical thinking competencies tied me in knots. My first attempts were to focus on sourcing, and given my Canadian context I headed to The Big Six (apparently they are going for $245 on Amazon now). Surely Seixas and Morton would help me unpack just what exactly I was supposed to be assessing.

I’d suggest they didn’t do us any favours (from an assessment standpoint). Take a close read of this guidepost suggested by Seixas and Morton: “Sourcing often begins before a source is read, with questions about who created it and when it was created. It involves inferring from the source the author’s purpose, values, worldview, either conscious or unconscious.” I would suggest that within this guidepost we actually have aspects of sourcing, contextualizing, and close reading being described.

To be clear, this is an assessment problem. Not a historical inquiry problem. But given my goals, it’s a challenge.

Most teachers typically approach sourcing mostly with a focus on the “Sourcing often begins before a source is read” (I wish they would have explained what happens in the not-often cases). I say this because this was the way that I was generally taught, and how I generally taught the process…and typically using this source metadata, “infer from the source the author’s purpose, values, worldview, either conscious or unconscious” (Though here I will point out that Seixas and Morton actually suggest to “infer from the source” rather than “source metadata”, or answers to those “before the reading begins” questions. I think that’s probably intentional as I try to describe the issue with the latter approach below)

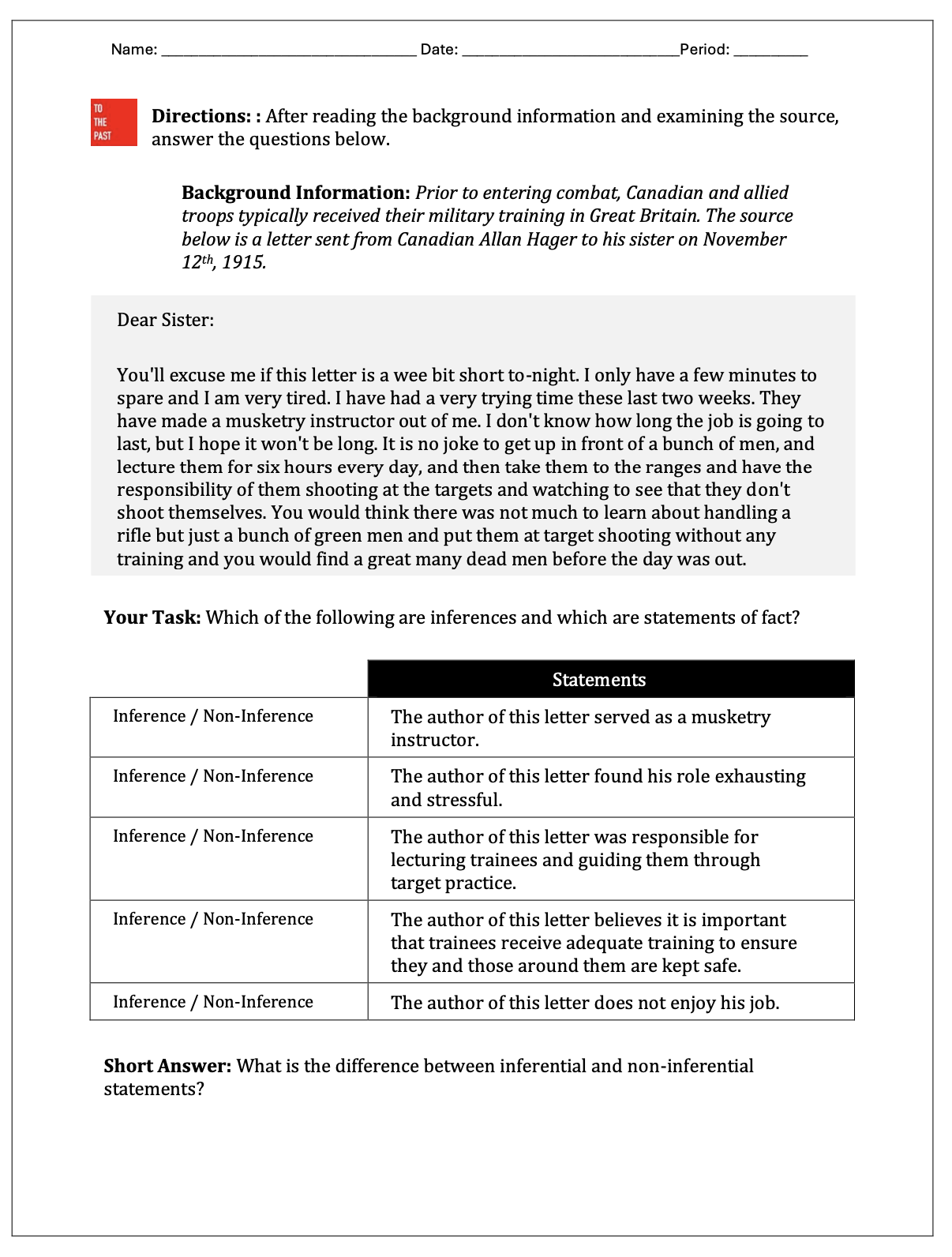

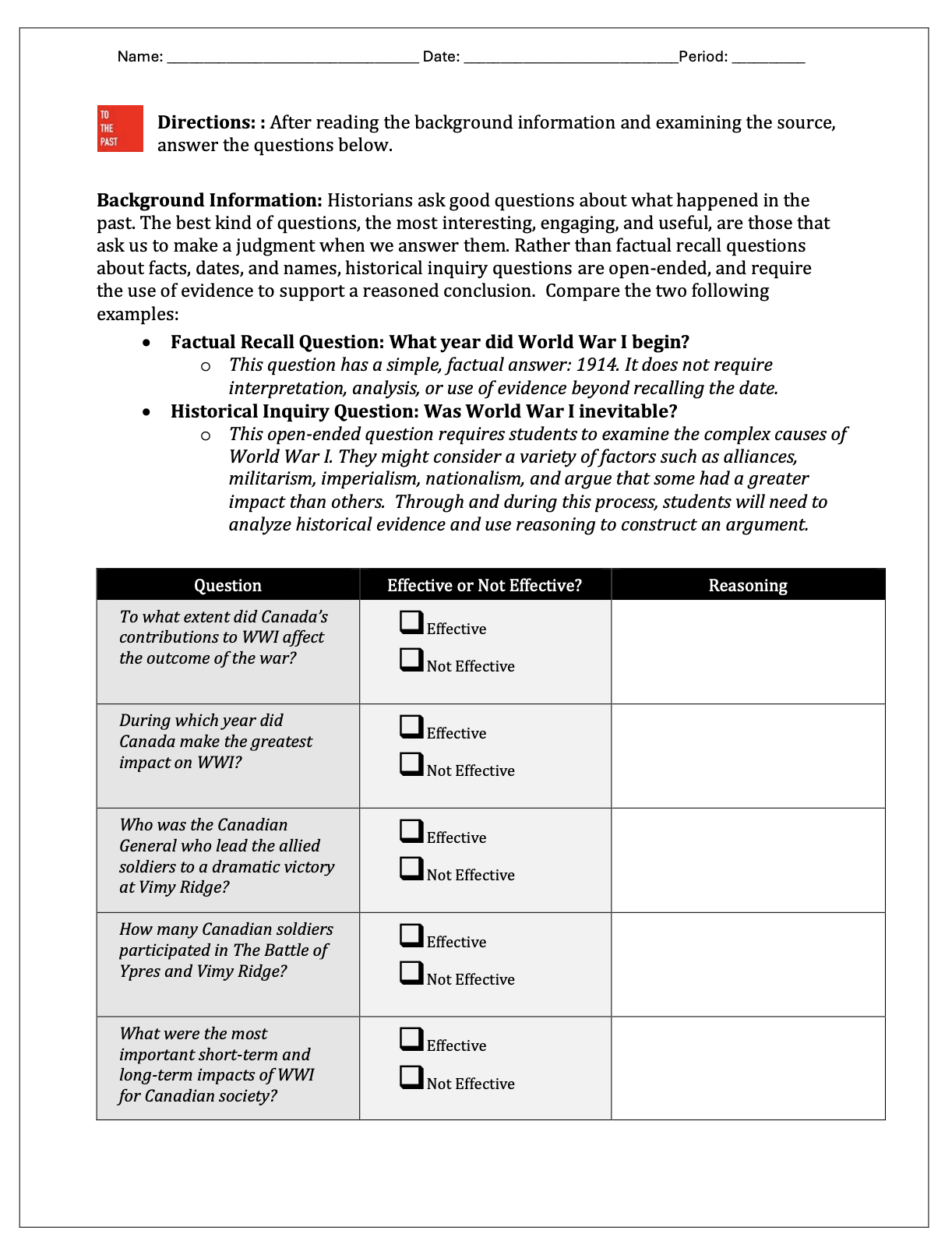

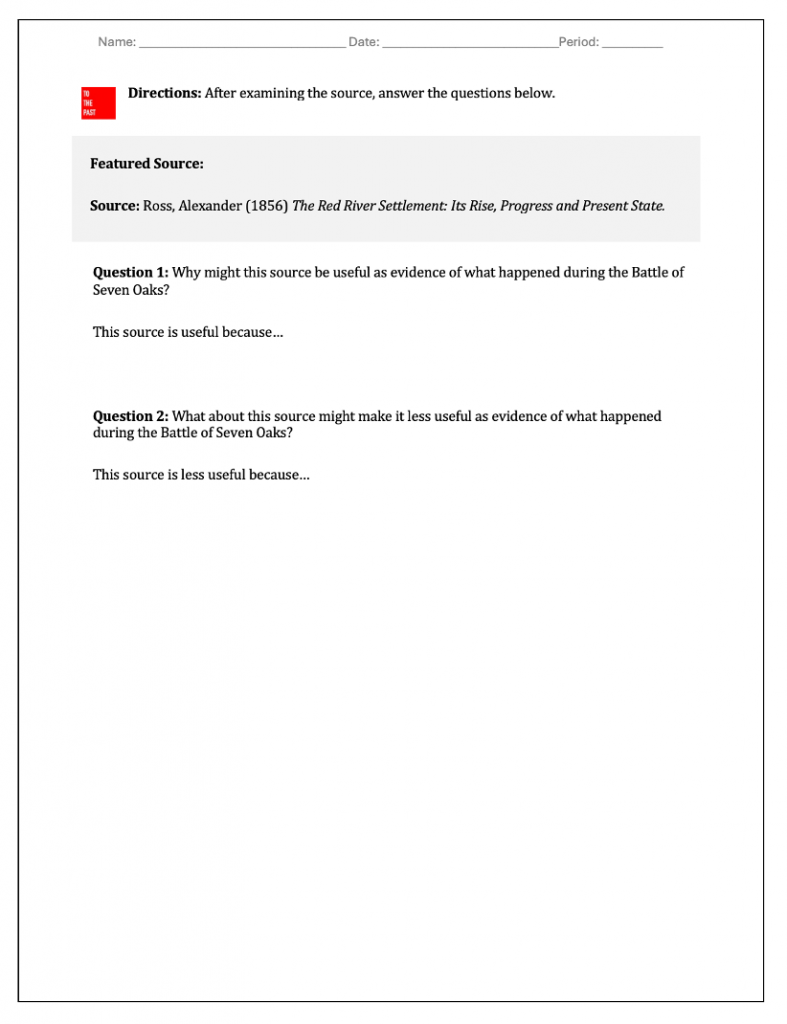

Let’s take for example an assessment I drew up modelled after the Stanford History Education Group’s Slave Quarters model.

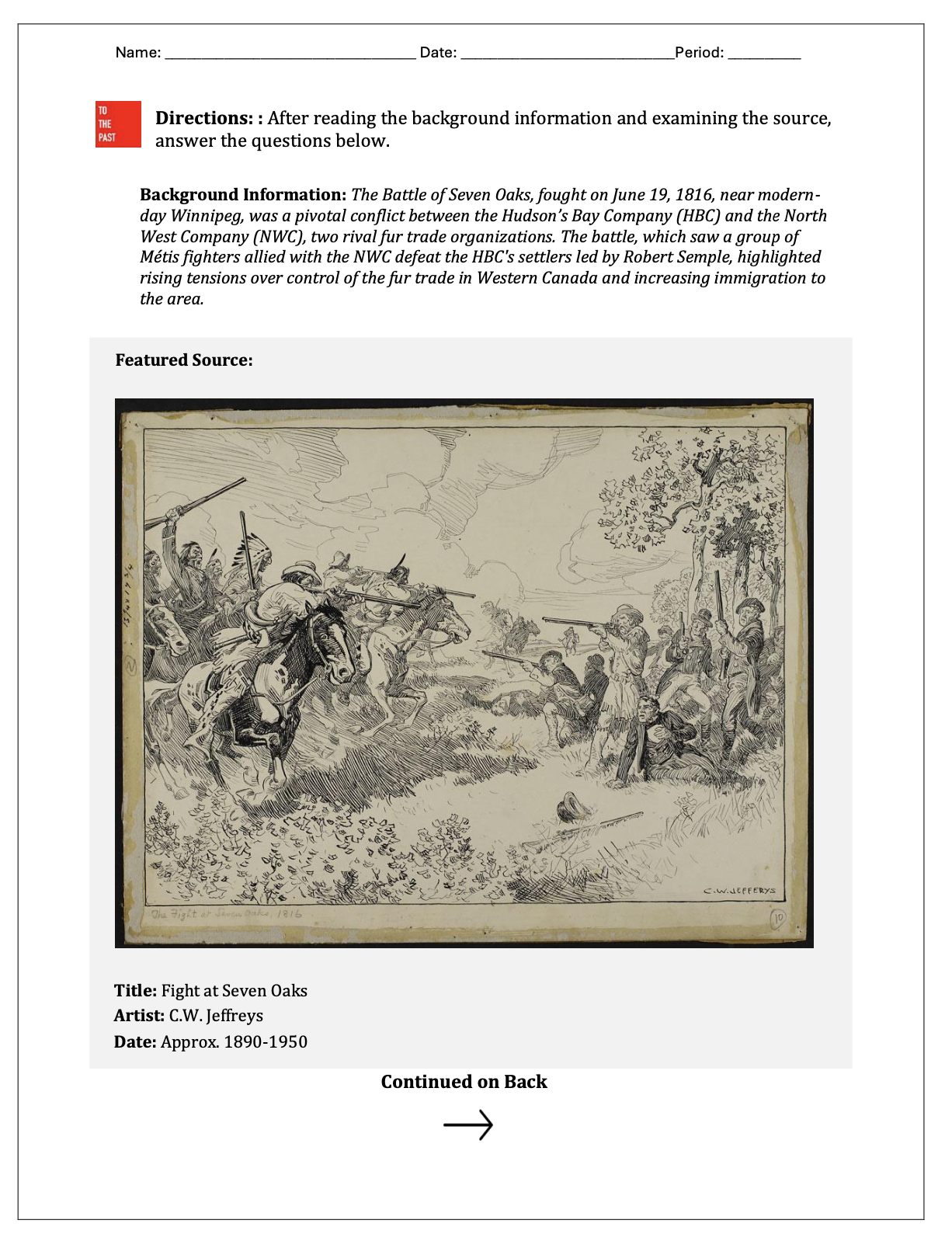

Here, I have removed the actual source, just to see what it would look like if we had students make their assessments from metadata. It’s pretty slim pickings. Students can’t really do much with the provided metadata because they likely don’t know anything about Alexander Ross, his role or occupation, whether the document is a book or memoir or journal, whether he was an eyewitness, or what was his role/relation to the 1816 Battle of Seven Oaks in the Canadian Northwest.

Let’s say a ridiculously keen grade 9 student pipes up: “Since Ross as an English language name derived from Gaelic, common in Scotland it is likely that Ross might report from a settler perspective, And given that we know that many settlers held indigenous peoples in low esteem, he likely believes that the settlers at seven oaks were justified in establishing their settlement and will probably be biased against the Métis” (I should point out here, that this example of “sourcing” is really just contextualization, or operationalized background knowledge, and in fact I believe that most sourcing is simply that, thus, background knowledge is important).

But I can’t expect all students to have a background in linguistics. So if I want students all to take a stab at sourcing, er… contextualizing this source, regardless of their background knowledge, then perhaps I need to provide it alongside Ross’ letter. How much do I include? If I really spell it out, am I just assessing reading comprehension as I direct them to some interesting background knowledge which might just be, wink-wink, useful in answering this question. I opted for a fairly dispassionate approach:

But back to our student’s assessment of Ross: “Since Ross as an English language name derived from Gaelic, common in Scotland it is likely that Ross might report from a settler perspective, And given that we know that many settlers held indigenous peoples in low esteem, he likely believes that the settlers at seven oaks were justified in establishing their settlement and will probably be biased against the Métis”

Would you be happy with that answer? For me, I’m conflicted. I do want students to attend to source metadata, keeping it mind as they work through evidence. However it also seems to rely upon vague stereotyping (regardless if described stereotypes prove to be accurate, and it sure does in Ross’ case). Gary Howells, working out of the UK puts the point quite neatly, describing “glib, yet reasoned and substantiated responses”:

Our hypothetical student is not wrong necessarily, but I don’t think this is the type of deep thinking that we are aiming for. The “before reading” phrasing is useful pedagogically (it gives students an entry point), but it also flattens the process into a checklist item. Students think: “I’ve sourced it, now let’s move on,” instead of hypothesizing, and then continuing to refine their sense of perspective, reliability, and purpose as they engage deeply with the text itself. Experienced historians (as far as I know) likely “source” before, during, and after reading, constantly looping between metadata and content. So, what would the assessment look like with the text provided?

Historians don’t disregard sources because of their real or perceived biases. Reading Ross’ account is rich reading because of its one-sidedness. His description of the battle is full of loaded language, sharply revealing “the author’s purpose, values, and worldview, either conscious or unconscious”. And it is here that much more interesting conversations can be found.

And so perhaps we might opt to pursue the following lines of questioning

- Pre-reading sourcing: “What might you predict about Ross’ point of view based on the information you have so far? What limitations are there to this prediction?”

- Post-reading sourcing: “Now that you’ve read the source, how does Ross’ language confirm, complicate, or contradict your initial thoughts about his perspective and reliability?”

But ack, I’ve been sucked into the wormhole of the bias trap, and regardless of whether this is a better way to approach the evaluation of sources, I certainly don’t want to give students the impression that historians are on a never ending quest to “spot the bias” as though they were Pokemon trainers intent on “catching them all. I’ll leave it to Ruth Sandwell who suggested the same so eloquently in 2003: “discussions of bias, though certainly valuable in some areas of historical study, as applied to the study of primary documents serve in most cases only to reduce students’ potential for understanding history…Examined through the lens of ‘bias,’ the complexities of historical interpretation and analysis instead get reduced to rigid, simplistic and stereotyped impressions that students might have about the self-interest (itself a profoundly historical concept) of the person who created the document”

So where does that leave me:

- I don’t really know what sourcing is. Or, perhaps more accurately, I think I have a pretty good idea, but my conceptualization might defy easy targetting in assessments.

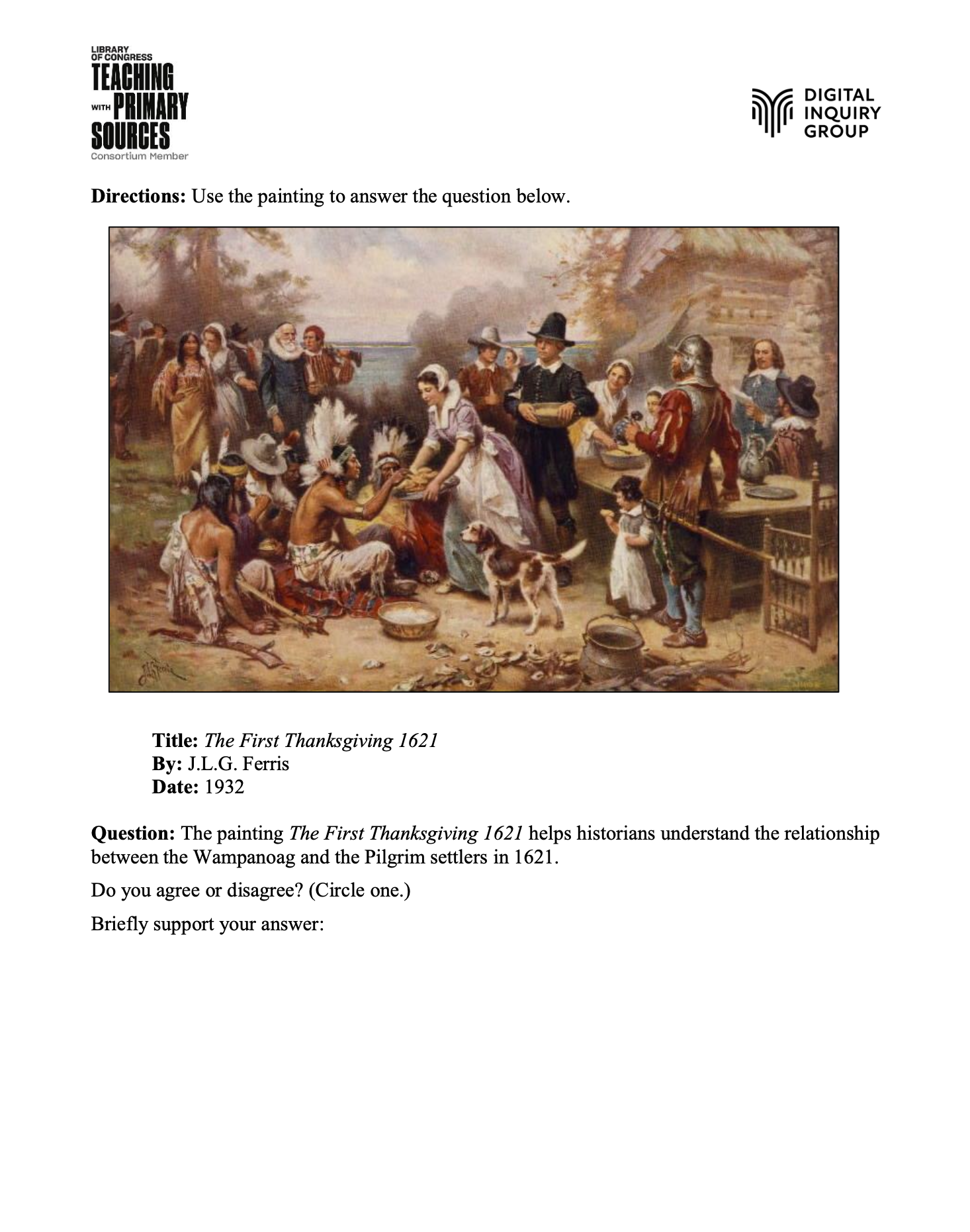

- I want students recognize that sources are not simply not neutral windows into the past, but rather situated accounts shaped by the context, perspective, and purposes of their creators. And so attending to perspective is important. But, I’d really love to move sourcing beyond “A First Thanksgiving, “Ah, there’s a discrepancy between event depicted and the date of source creation” or “This source is not reliable because of such and such stereotype or identification of self interest”.

I’ll explore a few examples in our next post.