WHAT IS TRULY “ACTIVE” LEARNING?

“Who on earth could be against active, meaningful learning and in favour of passive, meaningless learning?” – Kieren Egan, Getting it Wrong from the Beginning

We misuse words. All the time. Several years ago, Grant Wiggins illustrated this when he investigated the conflating of strategies/tactics/skills within literacy education. I, like Grant, enjoy clarity of language. And in education, well, clarity is sometimes rare (another favourite? Problem-based learning, inquiry learning, and project-based learning are often used interchangeably, or even simultaneously, ie. “I am really excited about project-based learning, and so my Social Studies 10 class is engaging in problem-based inquiry learning challenges.”)

Another problematic set of terms was brought to my attention when reading Kieren Egan’s book Getting it Wrong from the Beginning. His illumination of how teachers understand active learning as opposed to passive learning was particularly striking:

“What does it mean to distinguish forms of learning as active and passive? Well, at one level we all know: they are terms used to distinguish lifeless, inert, boring practices from their opposite. But why “active” and “passive”?” (66)

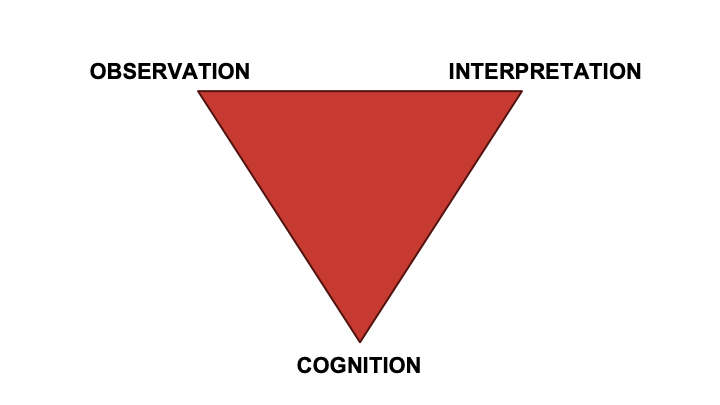

What teachers typically understand as active is more simply, physically active learning in the classroom. That is, ‘hands-on’, bodily kinesthaetic focused activities: hands-on, bodily kinesthetic focused activities: manipulating cubes, tableaux/skits, model building, laboratory work.

And this is understandable. Egan notes that “we can see physical engagement better than intellectual, there is a tendency to move increasingly in that direction.” And while “active” still carries connotations of constructive, imagination-triggering, and meaning-making activity, the label often only gets placed on learning activities in which we can see physical activity. And because the alternative is passive learning, and by that we mean, rote, transmissive, boring, lifeless, etc… a classroom filled with physically active students is necessarily a superior learning environment.

However this is problematic on several levels. “Is that child sitting and reading active or passive? Is the child imaginatively transported by a story the teacher is telling active or passive?” (66) The students don’t seem be visibly doing much at all. For another example, imagine students investigating primary sources related to the cancelling of the Avro Arrow. They read around the document, assess perspective, corroborate sources, build historical hypotheses and conclusions, support them with evidence. Visibly students seem far more “passive” than those creating skits, model-building, manipulating cubes…In fact an observer may be disappointed to see students sitting in rows, studying silently but for the rustle of papers. Yet I would argue that these students, even in the still quiet are engaged in exemplary active learning. Hands-on does not necessarily mean minds-on (Wiggins doing some heavy lifting in this post), and minds-on does not necessarily mean hands-on.

Moreover, an “active” classroom can hide truly “passive” activities. In guiding students in their reviewing for upcoming summative assessments I often use what many call “Person Bingo”. In this activity, students have a 4×4 chart filled with various questions. Students move about the room, asking their peers if they can provide an answer to one of the questions. Each of the question squares must be answered by a different student in the class.

When an observer views the classroom, it is active. Students are milling around the room, some with eager energy, while some congregate in large groups sharing their answers. The atmosphere is often loud, and filled with on-topic conversation. But this is not truly active learning. In fact, it is profoundly passive and transmissive.

We need to dig a little deeper past what is easily observed, and assess the actual activity being performed. While the questions could be higher order questions, for the most part when I lead this type of activity, the questions are simply questions of memorization; inert facts that they are not used for any greater purpose than passing the Social Studies 11 Final Exam! Students are not engaging in any higher-order thinking tasks such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. But. It looks active.

We should be looking past mere appearances to assess whether or not an activity is meaningful, imagination triggering, and, well, truly active.

A boring book which does not activate the mind…

An engrossing book which activates the mind with questions, connections, emotions of hopes and fears…

An unimaginative lecture, dry, and dull lecture…

An engaging lecture which activates the mind with new insights, connections and questions…

Even the activities with great potential for truly active learning (not like the activity that I described previously) can go awry. Egan points out that even John Dewey noted that “mere activity does not constitute experience” and that the “educative value of manual activities and laboratory exercises, as well as play, depends upon the extent in which they aid in bringing about a sense of meaning of what is going on” (67).

Caution before we praise, and caution before we criticize. Appearances can be deceiving.